Are Streaming Farms Really That Bad For Emerging Artists?

According to Rolling Stone, musicians could potentially be losing around $300 million per year due to streaming farms. It’s important to note that the streaming platforms themselves are not losing money, as streaming farms still need to use the streaming platform to operate. However, by inflating streams, they essentially steal money from artists that depend on organic streams. But what are streaming farms exactly? And can they actually benefit an artist’s career?

What are streaming farms?

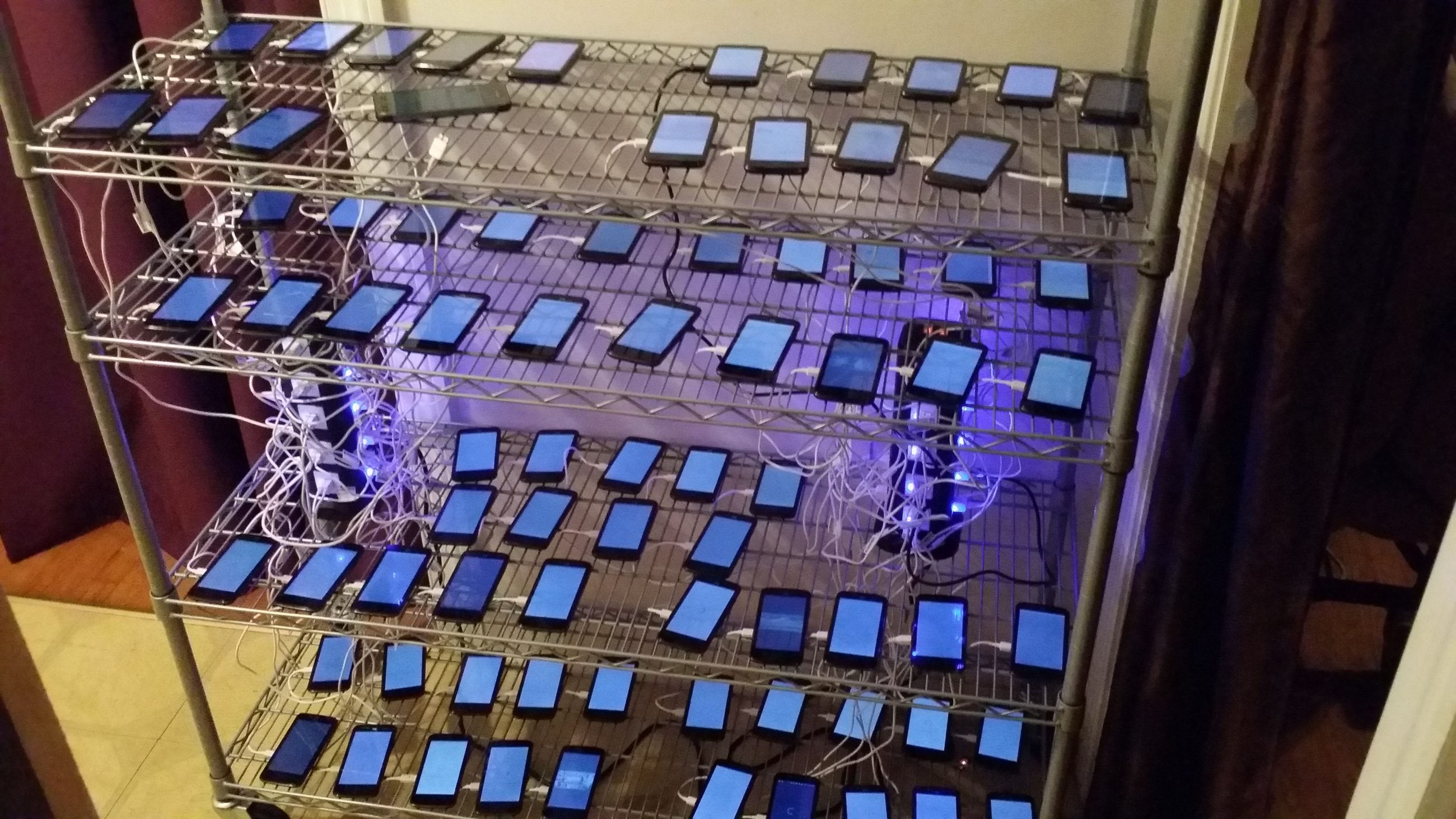

Streaming farms are services designed to inflate streams or add a lot of fake listens to a song. By taking advantage of the business model of streaming platforms like Spotify, they massively increase the number of listeners and in turn raise the hype surrounding the artist.

It is a “fake it until you make it” approach that, although useful for a few, is harmful to artists who do not engage in such activities. Sure, this is not the first time in history that artists have engages in such behaviour to jump-start their careers: funk group Vulpeck manipulated Spotify’s business model to make $20,000, while Soulja Boy broke through when he uploaded a song to LimeWire disguised as a hit song. Streaming farms, however, are a relatively new concept.

Unlike other methods, they do not require a person to be a tech or marketing genius to set them up. In fact, Vice journalist William Bedell managed to set up a streaming farm without requiring any mega-sophisticated equipment.

In his article, he mentions Peter Fillmore, the security consultant who was one of the first people to generate royalties using automated programs in 2013. He managed to earn about $1,000 in royalties and even topped the Australian charts of Rdio. To date, the biggest example of streaming fraud took place in 2017, when a fraudster from Bulgaria managed to make about $1 million from fake streams.

Inflated streaming services as a by-product of the attention economy

Nowadays, it’s extremely easy to find a streaming farm, ready to inflate your numbers. Artists are attracted to them just because of how scarce attention is in what we call the “attention economy.”

According to Eric Dott, an associate professor of music theory at the University of Texas: “Under these conditions, the ability to command public attention has become a highly prized and highly lucrative attribute, important not just for content producers and distributors, but for advertisers and marketers as well.”

He continues, “On music streaming platforms, by contrast, the connection between measures of user attention and financial compensation is more direct, in that revenue is typically shared with rights holders on the basis of the number of streams.”

Therefore, inflating your streaming numbers not only affects your stats but also your actual revenue – and how much money you receive in your bank account. Furthermore, if a song gets enough streams, it can break into charts, land spots on editorial playlists, and even lead to organic listens.

According to Dott’s research, the “surplus artistic population” is competing for attention. Since the “financial wealth” as well as the “symbolic power” are in the hands of a few, artists are ready to opt for less ethical measures. These artists are desperate to make a splash, and, despite the “diminished role of online gatekeepers,” they are still struggling to make ends meet. Streaming farms are seen as a way to level the playing field to win in a market climate that failed them.

Are streaming farms worth it?

This analysis raises the question: Can streaming farms be beneficial? Is it worth paying a company to inflate your streams if it increases your chances of going viral?

While it may initially seem like a good idea, streaming farms are sabotaging musicians with “honest” streams and doing more harm than good when it comes to overall artist payouts. According to a Rolling Stone article, “three to four per cent of global streams are illegitimate streams…That’s around $300 million in potential lost revenue moved from legitimate streams to illegitimate, illegal streams.”

Moreover, faking hundreds or thousands of listeners could backfire. Music professionals can spot fake streams from a mile away, leaving you in a precarious position when applying for legitimate opportunities.

Things like random top cities, a weird selection of similar artists and a monthly listener-follower ratio that makes no sense are clear indications of artists with inflated streams. Word travels quickly and can lead to a bad reputation that you definitely do not need in an industry as connected as the music industry.

All in all, while engineering your own breakthrough via streaming farms might seem like a good idea, it can do far more harm than good. A clear focus on long-term goals and opportunities, coupled with a community of true fans is, by far, the superior way to engineer your success.